Why review assessment practice?

The pandemic accelerated digital transformation of assessment for some institutions and caused others to question not only how they do things but whether they are doing the right things?

Assessment and feedback forms a significant element of staff and student workload and many studies have shown that students, in higher education, are less satisfied with assessment and feedback than with any other aspect of the experience.

This guide will help you determine what good assessment and feedback looks like in your context so you can benchmark existing practice and plan improvement.

Assessment and feedback landscape

Through consultation with universities, a survey and a review of the current literature we gained a picture of the UK assessment and feedback landscape in higher education in 2022.

View our assessment and feedback higher education landscape review.

In 2024, with insights from our assessment and feedback working group, we have explored emerging trends in assessment and feedback within the rapidly evolving landscape of higher education. Trends in assessment in higher education: considerations for policy and practice report sheds light on the challenges, opportunities, and innovative approaches shaping the future of assessment practices, particularly in the context of digital transformation and the integration of generative AI technologies.

Register your interest in joining our working group for assessment and feedback in higher education

About the examples in this guide

Each of the principles is accompanied by short case studies of implementation.

Where possible we have chosen examples where digital technology has been used to support and enhance good practice.

Previous research found good practice was often difficult to scale up because it required manual intervention or tools that were not interoperable. Our examples show innovative practice delivered at scale and using open standards to facilitate seamless integration with existing tools and administrative systems.

Assessment and feedback: direction of travel

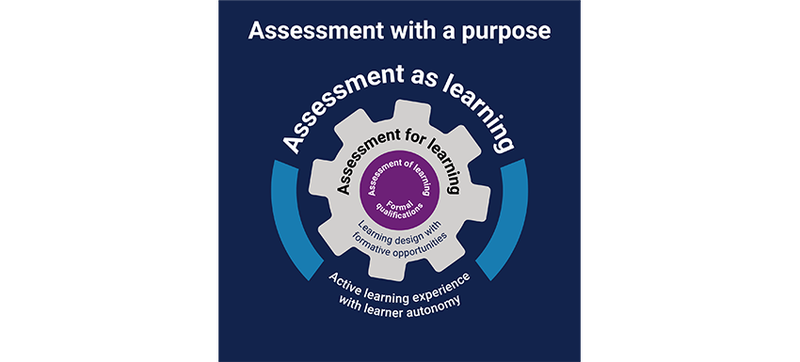

For a number of years assessment and feedback practice has been on a trajectory away from assessment of learning to what is termed assessment for learning.

Key to this has been helping students monitor and regulate their own learning and trying to ensure that any feedback activity feeds forward leading to future improvement.

Current assessment practice increasingly includes activities that could be termed assessment as learning. The very act of undertaking assessment and feedback activities is an essential part of the learning process.

All three aspects of assessment still need to happen but we are thinking differently about the relationship between them.

- Assessment of learning describes the institutional quality assurance processes that lead to students acquiring some form of verified credential.

- Assessment for learning is the overall learning design, ensuring we are assessing the right things at the right time with plenty of formative opportunities to feed forward. This is the cog wheel making everything revolve.

- Assessment as learning is a learning experience where the formative and summative elements work well together. Tasks appear relevant, students can see what they have gained by undertaking the activity, they feel involved in a dialogue about standards and evidence and the continuous development approach helps with issues of stress and workload for staff and students.

Text description for assessment with purpose graphic

- Purple centre - the inner circle represents assessment for learning the institutional quality-assured processes that lead to a qualification.

- The middle cog represents assessment for learning learning design emphasising formative opportunities that feed forward to future improvement.

- The outer circle represents assessment as learning the lived experience of students and staff when active learners contribute to decision-making and are able to monitor and regulate their own learning.

- Purple centre - the inner circle represents assessment for learning the institutional quality-assured processes that lead to a qualification.

- The middle cog represents assessment for learning learning design emphasising formative opportunities that feed forward to future improvement.

- The outer circle represents assessment as learning the lived experience of students and staff when active learners contribute to decision-making and are able to monitor and regulate their own learning.

Beyond the Technology podcast

Listen to our series on rethinking assessment and feedback from the Beyond the Technology podcast:

- Rethinking assessment and feedback - how the landscape is changing

- Rethinking assessment and feedback - providing personalised feedback at scale

- Rethinking assessment and feedback - creating a shared vision

- Rethinking assessment and feedback - unlocking the power of comparison based feedback

- Rethinking assessment and feedback - shifting to digital assessment

- Creative approaches to assessment - optionality

Introducing the seven principles

Educational principles are a way of summarising your shared educational values as a college or university. They serve to guide the design of learning teaching and assessment.

A well-thought-out set of principles:

- Describes a shared set of values and a vision

- Summarises and simplifies a lot of research evidence on good pedagogic practice

- Provides a benchmark for monitoring progress

- Serves as a driver for change

Principles offer a robust way of gaining ownership and buy-in and they need to be written in a way that requires action rather than passive acceptance.

Our seven principles

- Help learners understand what good looks like by engaging learners with the requirements and performance criteria for each task

- Support the personalised needs of learners by being accessible, inclusive and compassionate

- Foster active learning by recognising that engagement with learning resources, peers and tutors can all offer opportunities for formative development

- Develop autonomous learners by encouraging self-generated feedback, self-regulation, reflection, dialogue and peer review

- Manage staff and learner workload effectively by having the right assessment, at the right time, supported by efficient business processes

- Foster a motivated learning community by involving students in decision-making and supporting staff to critique and develop their own practice

- Promote learner employability by assessing authentic tasks and promoting ethical conduct

Applying the principles

The principles offer an actionable way to improve learning teaching and assessment and can be applied to any aspect of learning design.

There is no one size fits all approach. You need to decide what the principle means in your context and how best to apply it to the learning experience in your organisation. Our self-assessment template (.docx) allows you to adapt the principles to your own context. You can also download the self-assessment template as a pdf.

Do principles change over time?

Principles need to evolve over time if they are to reflect current education research and remain aspirational and a call to action.

The usefulness of educational principles drew widespread attention when Professor David Nicol published a set of principles for good assessment feedback practice as part of the Re-Engineering Assessment Practices (REAP) project in 2007.

Many education providers saw the value and adopted the idea so there are various sets of principles in the public domain (see ESCAPE assessment principles pdf). Almost all of them are based on the basic REAP principles.

Our 2021 principles reflect the greater prominence of issues such as accessibility and inclusivity in current thinking. Where we continue to champion examples of good practice that were recognised some time ago, it is with a new perspective on why and how certain approaches are more effective than others.

It is too early to judge how long this set of principles will last. At the moment they represent a call to action and a manifesto for change. We very much hope to find that in five years time they are no longer aspirational and require another refresh.

Related resources

Beyond blended: rethinking curriculum and learning design - a guide to support curriculum teams consider pedagogic differences between in place and online learning and the considerations for assessment and feedback.

QAA Hallmarks of Success Playbook: Assessment in digital and blended pedagogy - A useful guide to develop a shared understanding of assessment and feedback practices that are relevant to and support teaching and learning. It examines what success looks like in a digital and blended environment, barriers that may be encountered and how they can be overcome. The playbook can be used to drive discussions about assessment as learning, feedback and feedforward practices, as well as considering quality enhancement, moderation and academic integrity.

Assessment ideas for an AI-enabled world (.pptx) - Codesigned with the sector, we've produced a set of postcards to provoke discussion and reflection around assessment approaches in higher education. Each idea postcard outlines the type of assessment task, key characteristics and appropriate formats.

Principle one - help learners understand what good looks like

Why is this important?

Students undertaking an assessment need to understand what is required of them and the criteria against which their performance will be judged.

This sounds self-evident but many learners find it difficult to derive this information from the available sources such as course and module handbooks. Even where criteria and grade descriptors are provided, they may be couched in academic language that requires some skill to interpret.

It helps to have a common template for assignment briefs, so that the essential information is presented, in plain English, in a consistent way for each assignment.

Feedback for learning: a comprehensive guide, an e-book by FeedbackFruits, gives useful guidance on designing rubrics that support active learning. It explains how to create a rubric that is relevant, unambiguous and serves as a bridge to future performance by avoiding traps that can result in a rubric becoming a task-focused checklist.

By implementing this principle you will, however, take this a step further and engage students in activities that allow them to create meaning from the criteria and engage in discussions about quality. You may ask them to rewrite criteria in their own words and compare their understanding with that of others. Later they may even define the criteria by which they think their work should be judged.

The role of feedback

The capacity to recognise and interpret feedback, and use this to lead to further improvement, is key to developing the ability to recognise what good looks like

Feedback provides information about where a learner is in relation to their learning goals so that they can evaluate progress, identify gaps or misconceptions and take action that results in enhanced performance in future.

Feedback should be constructive, specific, honest and supportive.

Effective feedback shouldn’t only focus on current performance or be used to justify a grade. It should also feed forward in an actionable way so the learner understands what they need to focus on in order to improve.

Feedback is conventionally thought of as a dialogue between student and tutor but it can come from a variety of sources. Self and peer feedback can be equally valuable and we discuss this further in relation to principle number 4 develop autonomous learners.

Ipsative assessment

Ipsative assessment is the idea that, rather than evaluating a learner’s performance against an external benchmark, we simply look at whether they have improved on their own previous performance. This is after all the most effective measure of learning gain.

At University College London this approach is proving useful with master’s level students and those studying MOOCs.

To grade or not to grade?

Defining what good looks like does not have to mean assigning a grade.

There is a school of thought that believes grading is counter-productive and diminishes students’ broader curiosity about a subject. Read more about upgrading in Jesse Stommel's article.

Diverse assessment formats and different customs and practices across disciplines may distort marks. Even without these complications, experts question whether it is possible to distinguish the quality of work with the precision implied by percentage marks.

Higher education does indeed operate without grading in some areas. We recognise the value of a doctorate without questioning whether the holder achieved a few percentage points more or less than one of their counterparts.

The absence of a grade can oblige learners to focus on their feedback and encourage deeper reflection.

Technology can help

Some of the ways technology can help:

- Making information about the assessed task and criteria available in digital format helps ensure it can be accessed readily on a range of devices. It also helps with applying a consistent template

- Having the information in digital format allows cross-referencing to a wide range of examples

- Use of digital tools makes it easier to give ‘in-line feedback’ so students can see to which section of their work a feedback comment refers

- Digital tools can support better dialogue around feedback

- Storing feedback in digital format increases the likelihood that students will refer back to the feedback in future

- Digital tools that support self, peer and group evaluation are all means of actively engaging students with criteria and the process of making academic judgement. You can find examples of this in the section about putting each of our principles into practice throughout this guide

Putting the principle into practice

Guidance and templates

Sheffield Hallam University makes all of its guidance and templates available via its assessment essentials website.

The University of Reading's A-Z of assessment methods (pdf) can help you choose an appropriate type of assessment

Adaptive comparative judgement

Assessing a piece of work objectively against a rubric is not easy even for an experienced evaluator.

Comparative judgement works on the principle that people make better judgements if they compare two items, and decide which is better, than if they try to evaluate something in isolation.

Repeated comparison of pairs ultimately allows the items to be rank ordered. This usually takes nine to 12 rounds of comparison.

Adaptive comparative judgement (ACJ) tools automate the process of presenting a group of assessors with pairs to compare. The items are initially selected randomly. Comparison between very good and very bad is obvious very quickly. The computer algorithm can then start to select the pairs that will most improve the reliability of the ranking so more effort goes into assessing those that are closely matched.

Research has been undertaken using this technique to compare the evaluative judgement of staff and students. It has also been applied to using artificial intelligence (AI) to partly automate marking of complex items such as essay scripts.

The most common application is, however, in engaging students with assessment criteria and ‘learning by evaluating’ to identify what good looks like.

Using ACJ tools to provide peer evaluation and feedback can provide learners with a rich body of evidence to help them improve their work.

ACJ is being used at many universities internationally. In the UK examples include use at Goldsmiths, University of London and the University of Manchester.

The technique is explained in this presentation and session recording, which includes a case study from the University of Manchester.

Developing research skills at the University of Waterloo

Students undertaking an education degree at the University of Waterloo have the opportunity to gain a research credential in their specialist area during their work experience placement.

To gain the credential, the students have to assess their own research against a research skill development framework and demonstrate, during a capstone interview, the evidence why their experience merits special recognition.

The process is supported by a structured workbook in the e-portfolio that allows students to engage with the assessment framework before, during, and after their individual research experiences. The workbook acts as the basis for receiving personal guidance and feedback to support independent study.

"Engaging in this work reinforced how influential even a small degree of reflection and feedback can be in supporting student success. Implementing these changes required minimal additional effort but had huge impact on the students’ ability to relate their experiences to the assessment framework."

Jeremy Steffler, University of Waterloo

Principle two - support the personalised needs of learners

There is no such thing as a standard learner. Disability, neurodiversity, cultural and religious background, work and family commitments and personal preference all play a part in shaping our experience of learning.

Moreover, these factors combine to make the learning experience individual. Disabled students are no more a homogenous group than learners that have been bundled together under the unhelpful label BAME (black and minority ethnic). In March 2021, the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities recommended that the UK government stop using the term BAME. The government is currently considering its response to the Commission's 24 recommendations.

Accessible and inclusive

Good assessment and feedback practice should allow a learner to apply their own individuality to demonstrating their knowledge and competencies.

We are increasingly aware of the need to make assessment accessible ie to ensure that people with disabilities do not face barriers because of the format or tools used. We need to promote similar awareness of the benefits of making it fully inclusive ie fair and equal to all students regardless of their diverse backgrounds.

Offering different means to demonstrate achievement of a learning outcome is an important way to comply with disability discrimination legislation. Applying this as a design principle goes further and enhances the overall assessment process to benefit all students.

Assessment designers need to be familiar with the law relating to accessibility and related guidelines such as WCAG (Web Content Accessibility Guidelines). For example, offering a digital paper as an alternative to hardcopy examination is only useful and legally compliant, if the digital copy meets accessibility compliance regulations. Software and resources used for digital assessment are legally required to meet the compliance standards. This needs to be considered in purchasing decisions and in-house development.

The emphasis on inclusivity relates to a broad agenda to ensure that our curricula are not skewed - for example to a particularly ‘white’ view of the world. There is much good work being undertaken on decolonising curricula and we need to ensure that assessment design reflects a global, multicultural perspective on the subject matter.

Compassionate pedagogy

Since the start of the pandemic there have been growing calls for us to develop more ‘compassionate pedagogy’.

As online classes have taken us into one another’s homes, teachers have gained a different kind of understanding of the conditions under which students study and the competing demands of work and family they have to juggle.

Digital poverty is only one aspect of this, time pressures and access to a suitable place to study are equally relevant and need to be factored into how we design learning and assessment.

Inclusivity means that no one’s socio-economic background should be a barrier to learning.

Promoting mental health and wellbeing

Promoting mental wellbeing is high on the agenda amid survey evidence from higher education that both student and staff mental health has declined in recent years. Assessment points are often the trigger for stress and anxiety related illness.

"Recognise that assessment times are often the breaking point for both staff and students."

–Sally Brown, consultant

An approach that allows for individual needs, and is founded on compassion for the learner, can help.

This is a topic that cuts across a number of our principles. Implementing principles number five: manage staff and learner workload effectively and number six: foster a motivated learning community will also have a positive impact.

"When it comes to mental health and well-being, avoid tokenism - don’t offer me yoga sessions give me practical help."

–Sally Brown, consultant

Some of the ways technology can help

Using digital tools makes it easier to implement universal design for learning (UDL) guidelines by providing multiple channels and options for engagement with learning and assessment activities.

Digital technology offers a vast range of assistive tools that allow learners to respond to the same activity or content in a way that is adapted to their personal needs. Examples include screen readers and braille keyboards for blind students, video and audio captioning for learners with hearing problems, the ability to change font size and colour to support dyslexic students or certain types of visual impairment. Some locked down virtual desktops and third-party tools used for summative assessment do not permit the use of the assistive technologies required by some learners. This is an issue that should be fully investigated before using such tools.

Aside from these adaptations, taking a summative assessment in familiar surroundings using familiar digital tools, may prove less stressful than a traditional example setting for many learners. In some cases, formal examinations may be one of the rare occasions where a student uses a pen.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is enabling the development of ‘adaptive’ learning tools that respond dynamically to student responses in order to personalise learning pathways. Their main use is in formative testing. For example, a student can be presented with progressively more difficult questions based on what they answer correctly.

We are increasingly used to technology providing us with friendly reminders when we need to do something in many aspects of our lives. Digital tools provide various ways to give learners ‘nudges’ and reminders about upcoming deadlines and important due dates via email, text, mobile app or reminders in the VLE, helping to provide clarity and alleviate stress.

Putting the principle into practice

- For help with the basics, see our guide to getting started with accessibility and inclusion

- For regular updates see our accessibility blog

- You can also join our accessibility and assistive technology community groups

- You can listen to our Beyond the Technology podcast: using AI to support and enhance formative assessment

- Read this report from Advance HE - Assessment and Feedback in a Post-Pandemic Era: A Time for Learning and Inclusion

Making large classes feel small

A decade ago, the University of Sydney was unable to find a tool that could help solve the problem of engaging students with feedback and giving them personal care when cohorts could consist of thousands of students and learners felt lost in the crowd.

They developed a student relationship engagement system (SRES) which integrates with any learning management system using LTI and is now freely available to other universities. SRES is described as a ‘Swiss army knife for instructors’.

Today over 3,000 teachers are using SRES across more than a thousand courses at the University of Sydney. There were over a million student interactions with the portal in 2021 and 92.4% rated it as helpful. This is enhancing the learning experience of almost all 75,000 students at the University of Sydney with many more users worldwide.

Text description for elements of the student relationship engagement system (SRES) approach diagram

- Top row title is evaluative judgement with self assessment, peer feedback, teacher feedback and rubrics underneath

- Second row title is developing feedback literacy with appreciating feedback, making judgements, managing affect and taking action underneath

- Beneath these two rows is listed positive relationships, which results from the factors in the other boxes being implemented

- Top row title is evaluative judgement with self assessment, peer feedback, teacher feedback and rubrics underneath

- Second row title is developing feedback literacy with appreciating feedback, making judgements, managing affect and taking action underneath

- Beneath these two rows is listed positive relationships, which results from the factors in the other boxes being implemented

This diagram shows the elements that are important in contemporary approaches to helping students get the most out of assessment and feedback. Most importantly, they all exist within a wrapper of positive relationships with the tutor and others in the learning community.

SRES allows tutors to curated data from various sources in tailored dashboards that tell them what they need to know in order to best support their particular learners.

Data about logins and grades can be accompanied by other information that helps the instructor get to know the students. This could involve asking students about their preferences, what helps them learn and even their dreams and ambitions. Another example is that students can record an audio clip of how to pronounce their name.

These questions are embedded in the learning management system (using LTI) so to the learner they appear seamlessly alongside an introductory course in module information.

Highly personalised feedback can be created within the context of data such as whether the student has submitted on time or how they say they are feeling.

SRES also helps turn feedback into a dialogic process. Before submitting an assignment, students can say what they would most like feedback on, so they are primed to be more likely to engage with that feedback. Tutors can also close the feedback loop by asking students to respond and say what they thought about the feedback and what they will do differently next time. It is also possible to hide the grade until the student has responded to the feedback.

SRES also supports a wide range of peer-to-peer feedback activities.

Another use is to facilitate learning from both self and peer feedback. The portal can present results of student self-assessment alongside the evaluation given by their peers encouraging them to reflect on how this makes them feel and how they plan to improve on the next task as a result.

"SRES can provide some interesting ways to connect our feedback to student comments and to contextualise learning activities alongside students’ own stated goals and expectations. I think that’s quite a powerful shift with the potential to help students take greater control of their learning."

–Ben Miller, University of Sydney

Closing the attainment gap at Brunel University

Brunel University implemented digital open book assessments as a response to the pandemic and discovered that this helped close the attainment gap for certain students. Students who entered the University with BTEC qualifications, particularly black students with a BTEC, did significantly better in terms of degree outcome than in previous years.

This improvement can be attributed to the change in assessment practice with the open book format being similar to their prior experience. Closed book examinations tend to benefit students with A-level qualifications who are used to being assessed in this way.

"Instead of sitting in a sports hall for three hours and having to rely on memory, students were able to use any resources available to complete the task – something that is probably more akin to what those with BTECs would have done previously."

–Mariann Rand-Weaver, Brunel University

Read the full case study in Jisc's rethinking assessment report.

Supporting remote placement students

At Murdoch University hundreds of nursing students each year undertake a rural or remote clinical placement often up to 3000 km from home.

This placement may be the first time that the student is away from family, friends and normal support structures for an extended period. The staff member monitoring the student’s progress is rarely in the same location as the student and internet connectivity cannot always be relied upon.

The University uses its PebblePad e-portfolio tool to help connect with, and support, the learners.

As a result of codesign discussions with students, compulsory reflective assessments about their clinical experiences, have moved from written format to video blogs. Students can record the vlog anywhere and upload them to PebblePad later to be shared with on-site and remote assessors.

These ‘vlogs’ allow for individual creativity and personal connection as the tutors are now using the vlog format to provide feedback to the learners.

Beyond the Technology podcast

In our podcast on rethinking assessment and feedback, Danny Liu and Benjamin Miller speak about how they are adapting their assessment and feedback practices at the University of Sydney and how their use of the student relationship engagement system (SRES) has helped to solve the problem of engaging a large number of students with personalised feedback.

Principle three - foster active learning

Active learning has been a key tenet of curriculum design and learning space design for several years. Approaches to teaching have evolved in response to evidence that techniques such as lecturing, in contexts where students are passive recipients of information, are highly ineffective.

Building in formative assessment opportunities greatly enhances the effectiveness of learning activities.

The use of quizzes delivered via mobile devices during lectures, is a common example.

"To unlock the power of internal feedback, teachers need to have students turn some natural comparisons that they are making anyway, into formal and explicit comparisons and help them build the capacity to exploit their own comparison processes."

–Professor David Nicol, University of Glasgow

Active engagement with learning resources

We tend to think of active learning as something that involves interaction with a teacher or with peers but engagement with learning resources also offers opportunity for learners to evaluate their own understanding.

Interactive questions embedded in online textbooks is an emerging area that has considerable potential for learning enhancement.

Even in the absence of sophisticated digital tools, teachers can include discussion points for example by linking the prompts to a discussion thread in material on the learning platform.

Research by Professor David Nicol at the University of Glasgow suggests we have previously focused too much on feedback comments, and the dialogue around them, as the main mechanism by which students evaluate the quality of their own work. He believes that comparison with learning resources can be equally valuable in building student capacity to plan, evaluate, develop and regulate their own learning.

"Importantly, this research helps move our thinking away from teacher comments as the main comparator to a scenario where the teacher’s role is to identify and select a range of suitable comparators and to plan for their use by students. Possible comparators are numerous and might include videos, information in journal articles or textbooks, peer works, rubrics and observations of others’ performance."

–Professor David Nicol, University of Glasgow

Time to revise

An area that receives little attention in learning design is how students prepare themselves for summative assessment. What revision strategies do they employ and what resources do they use?

"Revision is an under emphasised area. It is a transition point where you make sense of what you studied and recode it in a way that enables you to answer questions. We need better revision materials and we need to allow students time to revise."

–Simon Cross, Open University

The Open University, UK recognises this and carries out an annual survey on student experience of assessment, feedback and revision (SEFAR). It concludes that revision and examination represents a distinct phase of learning but it remains challenging to determine effective analytics for this phase that can help inform better learning design.

The most conclusive finding was that the use of sample papers for practice appears to improve exam question literacy. Conversely, lack of engagement with these resources could be a trigger that a student requires some targeted support.

"What some of my professors did was this Microsoft Teams thing with me directly, where it was basically FaceTime, and I was able to go through any questions from past exam papers that I had issues with, and any questions that I had to clear up. And that was really useful, because it took the pressure off."

Second year student

Some of the ways technology can help

The use of quizzes delivered via mobile devices during lectures, is a well-known example of formative testing. It can be used to check whether most students have grasped key concepts and allow the lecturer to adapt the session if further explanation is required.

Interactive questions embedded in online textbooks is a more recent development. Research shows this type of practice question can significantly enhance learning compared to straightforward reading of text

Video resources can be very engaging but difficult to navigate. Digital tools that help students bookmark and add notes to particular sections, foster active learning and aid revision.

Putting the principle into practice

The Doer Effect

Research from Carnegie Mellon University suggests a causal relationship between students doing practice questions while reading and enhanced learning outcomes. This phenomenon, known as the ‘doer effect’ has been replicated in very large-scale studies in other US universities. The studies show that formative practice enhances the learning effect by a factor of six compared to simple reading of the text.

The research findings are very clear. The main factor inhibiting embedding such practice questions in every online textbook is the work needed to generate the questions. A textbook for a semester long module may require hundreds or thousands of questions requiring both subject matter and question item authoring expertise.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a promising solution to this problem. A research study (pdf) based on well over three quarters of a million student-question interactions showed no significant difference in the difficulty of, or student engagement with, questions written by subject matter experts and those generated using AI.

Interactive presentation

Universities using Feedback Fruits software have access to a tool known as interactive presentation. The tutor can upload video content, such as a pre-recorded lecture, and lock specific moments in the timeline with practice questions.

Students have to answer these questions before they can continue to watch the rest of the video.

The teacher has access to an analytics dashboard to see which questions students struggle with.

Synote

Synote is an award-winning, open source application developed at the University of Southampton that makes video resources easier to access, search, manage and exploit.

Imagine trying to use a textbook that has no contents page, index or page numbers. Lengthy video recordings, such as recorded lectures, can be equally difficult for students to navigate.

Synote allows students to bookmark particular sections of a recording and associate their notes with the correct section. Students can also take live notes during lectures, using Twitter, on any mobile device then upload them into Synote so they can be synchronised with a recording of the lecture.

Principle four - develop autonomous learners

It is often said that one reason students tend to express a relatively high level of satisfaction with lectures, is the fact that they don’t need to do anything during a lecture.

The remark is not entirely tongue-in-cheek. Tutors frequently complain that students see themselves as passive recipients of learning content. Similarly, in relation to assessment, some learners view it as the tutor’s role to deliver feedback to them.

Developing students’ ability to self-regulate and manage their own learning is a key goal of effective learning and assessment design. We also touch on this in relation to principle number one help learners understand what good looks like and principle number three foster active learning.

Activities that involve reflection and self, peer and group evaluation all work towards this goal.

The power of comparison

Many studies have observed that students appear to learn more from generating feedback for their peers than they do from engaging with peer feedback comments provided for them.

Research by Professor David Nicol, at the University of Glasgow, suggests this is because when students review their peers’ work, after producing their own, they make comparisons of the peer’s work with their own and this activates powerful internal feedback. Such comparisons can generate valuable learning whether the work of the peer is stronger or weaker than the reviewer’s own.

"Internal feedback is the new knowledge that students generate when they compare their current knowledge and competence against some reference information."

–Professor David Nicol, University of Glasgow

A study comparing peer and tutor feedback (Nicol and McCallum 2021) found that students of all abilities were able to identify all areas for improvement that the tutor identified as well as areas that the tutor did not mention. However, to match the tutor feedback, the students had to make multiple sequential comparisons (ie compare more than one peer work with their own).

This research suggests that well-structured peer review activities can reduce teacher workload and generate more and better feedback for learners.

"A basic recommendation is that teachers reserve their comments until after students have made comparisons against other information sources, as this will reduce teacher workload, ensure that what they provide is maximally relevant and necessary, while at the same time it will foster student independence."

–Professor David Nicol, University of Glasgow

Self-paced learning

Most educators recognise the importance of developing learners’ capacity to self-regulate and the role that engagement with feedback plays in this. Our efforts in this area are however, sometimes at odds with a fixed regime of content delivery via lectures and a rigid assessment schedule. Inevitably, some learners struggle to keep up whilst others are insufficiently challenged.

Higher education could do more to encourage self-pacing within bounded limits, such as an individual module. Students could be allowed to test their knowledge when they feel ready and resubmit until they have mastered a topic.

There may be lessons to be learned in this area from the school sector. The modern classroom project suggests the following classification of learning and assessment activities:

- Must do: non-negotiable tasks covering core concepts and essential skills

- Should do: valuable opportunities to develop skills that will not prevent the student transitioning to the next stage of learning if there is a good reason for them to be excused

- Aspire to do: extensions for students who have already mastered the normal scope of the topic

Analytics to track progress help ensure that the group as a whole is on track. Sharing of aspects of goal setting and tracking can help students identify others to collaborate with or who can provide help.

Policies such as ‘ask three (peers) before me’ can encourage peer learning.

Similarly, assignment briefs can be split in two with half of the group addressing each aspect of the topic then teaching and learning from peers who did the opposite assignment.

"One really powerful way to keep students engaged and support their self-esteem is to build in motivation strategies that ensure students believe they can succeed with this newfound level of responsibility."

Kareem Farah, the modern classrooms project

Some of the ways technology can help

Early attempts to implement peer review found it could be time consuming to administer. Digital tools make it possible to implement peer review activities at scale.

Features such as allocation of reviews, linking to assessment criteria, managing anonymity and tracking which students have completed the work, are all easier in the digital environment.

Use of the open standard LTI means that tools supporting self, peer and group review can be seamlessly integrated into the learning management system.

Putting the principle into practice

Peer assessment at VU Amsterdam

Students in pharmaceutical sciences at VU Amsterdam (Vrije Universiteit) undertake peer assessment of one another’s reports as a mandatory pass/fail part of their course2.

The exercise is structured so that the students are undertaking the peer assessment individually but the report they are evaluating is the work of a group of three students.

The students are required to address each of the assessment criteria so the feedback is complete. Use of technology enables direct linking to the assessment criteria and enforcing the requirement to address each criterion.

Learners are also required to rate the quality of the feedback they receive from other peer reviewers.

This activity engages learners with the assessment criteria and also encourages them to reflect on the process of giving good quality feedback.

Feedback given by students matches well with instructor feedback. This means staff time can be saved by monitoring a random sample to ensure quality is being maintained.

This approach, whereby engagement with the feedback process feedback is an individual responsibility, works much better than previous initiatives where groups gave feedback on other groups.

"Unlike in previous years, there were no longer any complaints about the feedback process."

–Jort Harmsen, VU Ansterdam

Two stage examinations

It is not unusual for a learner to walk out of a formal examination and immediately think of something they should have done differently. Normally it’s too late but what if you had the chance to put it right?

Research by Professor David Nicol and colleagues at the University of Glasgow has taken this idea step further and researched the impact of a two-stage examination structure3.

In their model a student takes an exam and then completes reflective questions to surface their internal feedback about their performance. They are asked to identify any weaknesses they are aware of and any aspects of their work on which they would like to have expert feedback.

The students then take the same exam again but this time working in groups.

At the end of this stage, they answer another set of reflective questions, for example, about how the group answer differed from their own, whether the group discussion made them aware of strengths and weaknesses of their own answer that they hadn’t identified and which answer they thought was better.

The purpose of this study was to find out more about how students generate inner feedback through comparisons. The finding was that this process is very powerful.

"Invariably students’ self generated feedback comments based on the reflective questions were more elaborate and specific than the teacher’s comments. While the teacher gave general comments about the strengths and areas in need of improvement, the students were more likely to state exactly how the improvements could be made."

–Nicol and Selvaretnam (2021)

The fact that students undertook the work individually and reflected on their performance before engaging in dialogue, served to start them generating inner feedback so they gained greater value from the group discussion. The key to harnessing inner feedback is to make the process explicit using reflective questions to which students must respond in writing.

The researchers believe that the findings have broad applicability and that providing a rubric or high-quality exemplars as comparators could equally help students better evaluate the quality of their own work.

Professional learning passport for teachers

The Education Workforce Council (EWC) is the independent regulator for the education workforce in Wales. It has developed a professional learning passport (PLP) to enable newly qualified teachers to capture their learning and development and receive support from mentors.

EWC developed the passport using its e-portfolio tool. Teachers can capture any learning or experience that shows they are developing competence against the professional standards for teaching and leadership. Teachers reflect on experience, and plan learning in areas that need development, in an organic way that feels quite natural and unlike many formal assessment practices.

This approach prompts new teachers to consider all the learning experiences that occur during their working days from moments in the classroom, to discussion with colleagues, to formal training opportunities – and reflect on how these impact on their development as professionals and their teaching practice. The completed PLP enables the teacher to present their learning and development journey.

Principle five - manage staff and learner workload effectively

We need to ensure we are assessing the things that matter and doing so in a way that allows the student learning from each assignment to feed forward into future tasks.

Common problems to avoid are over-assessment and assessment bunching.

A programme of study is likely to be broken down into smaller modules. Each module will have its own learning outcomes and there may be overlap between them. If each module team designs its own assessment without reference to the overall picture, you may find that some learning outcomes are assessed multiple times and that assignments are ‘bunched’ at particular times of year.

Learners are not able to produce their best work if they have multiple assignments to complete within a short timeframe. A group of student union officers known as the academic integrity collective points to overassessment and bunching as factors that may panic students into cheating.

This type of bunching also puts stress on staff marking and grading the assignments.

We also need the right balance between formative and summative assessment. Applying our principles means designing in formative opportunities where students can generate feedback from a variety of sources and act upon it to feed forward into the future learning.

Students and staff should spend most of their working time on tasks related to enhancing learning. This means business processes need to allow them to access the information they need, submit assignments, enter marks and feedback and view information from different sources, easily and quickly.

Academic staff working with badly designed business processes often describe themselves as being on a treadmill with no time to stop and reflect how things might be done better.

Staff also need to be supported to use the available tools. For example, assignments submitted electronically by students may be printed out by the staff marking and grading them. There could be many advantages to marking online if staff were given the necessary tools and shown how to adjust the view to suit themselves and take advantage of features such as ‘quick mark’ options.

Some of the ways technology can help

Understanding the curriculum

A description of the curriculum in digital format can allow you to get an overview using only basic analysis, such as number and type of assignments per module, to see where some learners may be being over assessed.

A similar overview of assessment dates will reveal assignment bunching.

Personalising information

Many institutions now use apps that provide students with a personalised overview of administrative information such as timetable, assignment due dates etc that can help them manage their workload better.

For staff, it is increasingly common to have a personalised dashboard view showing the status of assignment tasks and their priority.

Workload management

Online workflows make it easier to manage team marking across large cohorts.

Digital feedback tools offer the possibility to reuse/adapt frequent comments to save tutors time.

Digital tools offer possibilities to generate and mark questions for both formative and summative development. The type of questions that can be created and automatically marked using the QTI (question test interoperability) open standard go far beyond basic multiple-choice and can include evaluation of what higher-order skills learners are using to come up with their answer.

Putting the principle into practice

Transforming the Experience of Students through Assessment (TESTA)

TESTA has produced guidance on revised assessment patterns that work.

The University of Greenwich map my assessment tool helps with planning, identifying clashes and modelling the consequences of change. The tool is available for others to use.

One-stop-shop EMA (electronic management of assessment) solution at the University of Wolverhampton

The University of Wolverhampton used the Jisc assessment and feedback life-cycle to help its analysis and planning to create an end to end solution for EMA (electronic management of assessment).

This ‘one-stop shop’ is built around the core tools of the Canvas learning management system and Turnitin academic integrity solution. The Learning Tools Interoperability (LTI) open standard is used to facilitate seamless interoperability throughout the workflow.

An assessment centre provides staff with an overview of all assessment tasks in their courses.

Staff can select and mark work from the assessment centre and are provided with information about approaching marking deadlines. They can also see whether marks and feedback have been published to the student record system and the students.

The project experienced few technical difficulties and focused much of its time on defining policy and addressing some inconsistencies in marking practice.

View a set of presentation slides and watch the session recording on this case study.

"This was not a data integration project. It was all about assessment processes, aligning the technology to the pedagogy and the policy requirements of the organisation. It was the policy, the data and the defining the processes which took by far the longest time."

Gareth Kirk, University of Wolverhampton

Timely feedback for large classes

The University of Utrecht department of law faces a ‘massiveness’ problem.

The department has 800 new students each year and the current learning design requires them to complete an essay each week. Feedback and grades must be returned within three days in order to feed into the next assignment.

This has to be managed with a team of two professors and 25 ‘correctors’ who provide feedback. The correctors are a combination of assistant professors, teaching assistants and third-year students.

The University has implemented Revise.ly feedback software to help solve this problem. The correctors use a shared comment set to ensure that the approach to feedback is consistent no matter who does the marking. Although the role translates as ‘corrector’ in English, all comments use a ‘feed forward’ approach to help with future improvement.

The tool is integrated into the learning management system using the LTI open standard. It can be used on any device and fits easily into the existing workflow, including incorporating it into workflows involving plagiarism-checking or peer-review.

Learners find the approach very helpful because the feedback is readily accessible and the structured approach means they can search what type of comments they want to see (eg focus on structure) and review this type of comment across different assignments. The search function was added at the request of the students.

Enhancing the effectiveness of personal tutoring at the University of Cumbria

Personal academic tutoring is an important feature in helping students adjust to university life and develop their academic potential.

The University of Cumbria supports 10,000 students a year in this way and turned to technology to address inconsistencies across different parts of the University.

Each learner now has a workbook in the e-portfolio system that is used to provide clarity and structure to the personal tutoring process and a more supported experience for the students.

An introductory ‘About You’ page allows students to provide background information about themselves. Each of the 30 minute meetings has a separate page and, in advance of each meeting, students are prompted to fill in questions that give useful pointers for discussion.

During the meeting, or immediately afterwards, the personal tutor adds notes summarising the discussion and providing signposting for the student to further help and support where appropriate.

Find out more about the University of Cumbria's experience of enhancing personal tutoring.

Principle six - foster a motivated learning community

"Feeling connected and valued really helps to improve learning as well as engagement."

–Danny Liu, University of Sydney

"Principles that foster human connection are vital. How we develop relationships and maintain connections with and between peers, have become vital questions. Creating a sense of belonging in the virtual classroom has far reaching effects."

–Ewoud de Kok, FeedbackFruits

"Collaboration is at its best when students truly believe they will have a greater chance of achieving their academic goals by working with peers."

–Kareem Farah, the modern classrooms project

This ties in with principle number two support the personalised needs of learners. Involving students in discussions around assessment practice helps make it more inclusive and allows students who may face barriers, for example, due to a disability, to voice their concerns.

Assessment literacy

Institutions commonly focus on developing learners’ study skills, graduate attributes and digital literacies but none of these fully addresses student understanding of, and engagement in, the assessment process.

Study skills resources tend to help students develop their assessment ‘technique’ through essay writing, presentation and preparing for exams rather than understanding the nature and purpose of assessment and feedback practice.

Engaging students as active participants in making academic judgement develops their assessment literacy and gives assessment a sense of purpose which is motivating.

Participating in discussions about assessment approaches, criteria and standards can help develop students’ academic judgement as well as developing skills important for employability. Self and peer review activities are the most active way of allowing students to practice making evaluative judgements.

Developing academic practice

It is just as important for staff to reflect on their assessment and feedback practice as it is for students to strive to improve their own performance.

New findings from education research and advances in technology may offer improved ways of implementing good practice even if the underlying pedagogy is still sound.

"We didn’t need to do anything different but we did need to do things differently."

–Elizabeth Hidson, University of Sunderland

Course and module teams may spend a lot of time discussing approaches at the curriculum design stage only for assessment and feedback to be left to personal choice.

"In a competitive and time-poor working environment, investing in developing new and challenging feedback practices can be the last item on the list."

–Dr Ian Davis, University of Southern Queensland

Feedback is the area that most often takes place in a ‘black box’. There may be little or no team discussion leading to inconsistency of approach and variation in the quality and quantity of tutor feedback.

Tutors who haven’t had the opportunity to discuss feedback practice with colleagues may produce feedback that is skewed towards either praise or correction or short-term and focused on the task in hand rather than developmental.

"New tutors often have a limited feel for what good feedback looks like or what standard of feedback, in terms of length and specificity, is expected. They may concentrate on proving their superior knowledge to the student rather than focussing on improving the students’ work in future."

–Transforming the Experience of Students through Assessment (TESTA)

Despite rigorous quality processes, marking and grading may still be subjective. In the absence of whole team approaches, tutors may develop tacit and personalised standards that lead to inconsistency and inequality for learners.

Listening to the student voice can reveal how the lived experience of assessment and feedback practice matches the expectation of course designers.

Some of the ways technology can help

Our digital experience insights surveys can play a part by showing how your students and staff are using the technology you offer, what is making a difference to their learning and working experiences and where improvements can be made.

Digital tools supporting self, peer and group evaluation can help develop student assessment literacy.

Digital storage of marks and feedback can simplify analysis to identify anomalies. Analytics about the types, quantity and timeliness of tutor feedback can stimulate discussion about what is most appropriate in each context and the equity of the learning experience across an institution.

Online communities of practice permit sharing of experience across a wider network than a single course or institution. Sometimes it can be easier to share ideas and get an objective view on a hard-to-solve problems with colleagues who are removed from the working practices and day-to-day politics of your own institution.

Putting the principle into practice

Find out more about our change agent network supporting student staff partnerships across the UK.

University College London (UCL) is one of the active participants in the network. The University has established a central team of digital assessment advisors and runs ‘assessment mythbusting’ town hall events and assessment ‘hackathons’. UCL also has appointed a group of student assessment design advisors to help develop and pilot new forms of assessment. Find out more about UCL's partnership approach to assessment transformation.

Streamlining global teacher training

The University of Sunderland runs an international teacher training course which attracts students from 60 countries. Assessment used to include a lesson observation carried out face-to-face in the classroom.

Improvement in the reliability of videoconferencing tools enabled the course team to develop the VEDA (video enhanced dialogic assessment) approach which won a university teaching award. This allows the lesson observation to be either recorded or live streamed.

Use of the open standard LTI Deep Linking allows the session to be recorded using the Panopto lecture capture tool and uploaded straight to the Canvas VLE (virtual learning environment). Data protection compliance is important as the videos contain images of children.

Course leader, Elizabeth Hidson found not only did this online viva-voce style assessment save on time and travel costs, it also facilitated improved professional judgement. Assessors spent more time and energy in the online space than was possible at the back of the classroom and the dialogue stimulated better reflective practice.

"Our ideas of ‘evidence’ have become more sophisticated and holistic based on better quality dialogue and professional judgements."

–Elizabeth Hidson, University of Sunderland

The initiative was introduced as a response to the pandemic but, as the candidate usually bears the cost of the assesser’s visit, there is interest in offering this option in future.

Assessing the process of thinking

We tend to focus on immediate peers when we talk about learning communities but academic development is also taking place at scale. Across France open standards and data science are being applied to improve assessment practice.

The French ministry of education uses digital technology to develop more authentic ways to measure traditional competencies and 21st-century skills.

These assessments don’t only provide information about whether the answer is correct. They capture a rich set of data that reveal the students’ thought processes.

Solving problems in mathematics and science requires students to use cross-curricular skills such as calculating, modelling, and scientific reasoning. Until recently, it has been difficult to measure these skills because traditional math and science assessments contain test items that are scored, based on a student’s final answer.

Using an extension of the open standard QTI (question and test interoperability), the ministry is developing PCIs (portable custom interactions) to deploy authentic assessments that measure skills such as creativity, problem solving, collaboration and critical reasoning. The questions cover a wide range of types including game-like situations and interaction with chat bots to measure creativity.

Researchers make sense of a vast amount of data derived from these digital tests by defining patterns based on what knowledge and skills are involved in answering each question and common types of error.

In simple terms, there is a difference between the activity pattern of a student who has conceptual understanding and knows how to apply it in context and another who achieves the same answer via trial and error or guesswork.

Large-scale research has the potential to deliver valuable insights to help learning designers. Read about large-scale mathematics assessment in France (pdf).

More immediately, the examples of authentic question types openly shared, can provide inspiration and a rich reference source for others to use.

If you thought that item banks and automated marking could only be used with very basic multiple-choice questions (MCQs) think again.

View a set of presentation slides and watch the session recording on this case study.

Principle seven - promote learner employability

Our thinking is influenced by Dr Yong Zhao. He suggests education, rather than trying to fix perceived ‘deficits’, by measuring against prescribed standards, should be cultivating individual strengths.

Employability, viewed from this perspective, can be seen as the ability to translate your uniqueness into value for others.

If higher education is to remain relevant in a changing world, it needs to demonstrate that our learning and assessment practices prepare people for the world of work and participation in democratic society.

Authentic assessment

There are frequent calls for assessment to become more ‘authentic’. By this we mean that the tasks which are assessed should reflect things the learner may have to do in real life.

"If the only worth of doing an assessment is to get the marks, you need to rethink it. Plausibility is important."

–Kay Sambell, University of Cumbria

Traditional assessment formats, such as essays or exams, don’t really mirror any other real-world situations.

Authentic assessment doesn’t only apply in subjects we traditionally think of as ‘vocational’. The skills we can test using formats such as closed book exams, which rely heavily on recall, are an equally poor fit with the working practices of academics or researchers of the future.

Authentic tasks are more likely to focus on deeper learning and the learner’s ability to apply their knowledge and skills. Give the learner some agency in deciding the topic and medium to be assessed, and you are moving towards the ideal of creating value from individual uniqueness.

Promoting ethical conduct

Academic misconduct features high amongst institutional concerns about assessment practice.

There is a perception that cheating and collusion are easier in the digital environment. However, such practices are generally only possible where the assessed task lends itself to finding an answer ready prepared. This is especially true now that the practice of purchasing an assignment written to order by an ‘essay mill’ has been outlawed.

"Instead of essays, alternative formats such as videos and presentations might also be considered. As well as better supporting disability, these formats might also provide greater authenticity to workplace environments and be less prone to cheating."

–Chris Cobb, chief executive, the Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music (ABRSM)

Not only is it harder to cheat at authentic tasks, they provide a sound foundation for a discussion of ethical practice. Academic writing and referencing can appear arcane whereas giving credit to the work of others in the world of business is a more familiar concept to introduce an understanding of ethics.

This is a topic that cuts across a number of our principles:

- Principle number one, help learners understand what good looks like is relevant. Student engagement with the performance criteria can help develop an understanding of the importance of acknowledging source material and intellectual property rights

- Principle number five, manage staff and learner workload effectively is important as pressure of over assessment can be a reason why students cheat

Putting the principle into practice

Our employability toolkit is a good starting point to find guidance and examples.

Policing a virtual shopping centre

The University of Northampton is using online scenarios to replace in-person training exercises for apprentice police officers. Videos of alleged robbery, shoplifting and suspicious activity in a shopping centre are accessed via the virtual learning environment (VLE).

Student responses to the scenarios are discussed in group webinar sessions which means that, for the first time, the whole class can learn from the experience.

The University has also created a mock courtroom scenario. Police apprentices present statements and are cross examined by two criminal barristers representing the defence and the prosecution.

Group member evaluation

In the world of work, overall team performance is as much a part of recognition and reward strategy as individual performance. Assessing a learner’s contribution to group work is thus a very authentic scenario but fraught with difficulty.

At Maastricht University in the Netherlands, students in the department of data science and knowledge engineering experience authentic learning and assessment from the start of their course. The department has a philosophy of problem-based and project centred learning. Students work in groups of six to seven to solve real-world problems.

The issues that arise will be familiar to anyone who has tried group learning. Students complain that some of them work harder than others with some students failing to complete tasks or handing work in late.

It can be hard for tutors to get to the bottom of the issues as some of the complaints are contradictory. Often, they don’t hear about the issues until a deadline is approaching by which point it is too late to intervene and improve the group dynamic.

The solution to the problem was to implement group member peer evaluation at a point when the group has had time to settle down but there is still time for the initiative to result in improvement.

Group member evaluation is done anonymously using a tool designed by FeedbackFruits in collaboration with a group of universities. The tool is integrated into the learning management system via LTI.

Learners have to evaluate themselves before they assess other group members. They then look at how their self-evaluation matches that of their peers and have the opportunity to discuss this with their tutor.

A rubric was developed to assist the evaluative process. The rubric has six categories: attending internal team meetings; responsibility; communication; interaction and collaboration; initiative and timely submission of assigned work. There is a descriptor equating to: acceptable; satisfactory or exemplary for each category.

Students were at first encouraged, but not obliged, to provide additional feedback in the form of a comment. It is now felt to be good practice to require further comment on a low score. The reason behind a low score on attendance may be self-evident but a poor score for ‘initiative’ can be less so.

Most students value the initiative and take it seriously although some take longer to build up trust in the practice. Some timid learners have had their confidence boosted to find that peers appreciate their ideas and think they should speak up more.

View a presentation and watch the session recording about this case study.

The economics of panic buying

At Stirling University an economics exam involving ‘doing the calculations by hand, from memory, in a cold sterile environment’ has been replaced by real-world problems requiring flexibility and creativity to address the issues.

First year students in 2020 were required to design strategic interactions to address the pandemic. Topics ranged from panic buying, hoarding and price gouging to vaccine uptake and sharing. Students were free to use their own choice of medium including blog posts, digital posters and videos

The boss wants an answer by the end of the day

The environmental science department at Brunel University London replaced a three-hour exam with a more authentic task. Students were confronted with what it feels like to turn up for work one morning and find your boss needs a report on a complex matter by the end of the day.

The assessed task was a complex question drawing on a wide range of information encountered during the course. The students had to demonstrate their working and provide references with highlighted annotations. They had seven hours to tackle the problem.

"You might think that the end product would be some incredibly long reports, which would add to the marking load, but part of the task was to make sure that the work was also concise and effectively communicated. It tested higher-order thinking skills and quality rather than quantity."

–Mariann Rand-Weaver, vice-provost (education), Brunel University